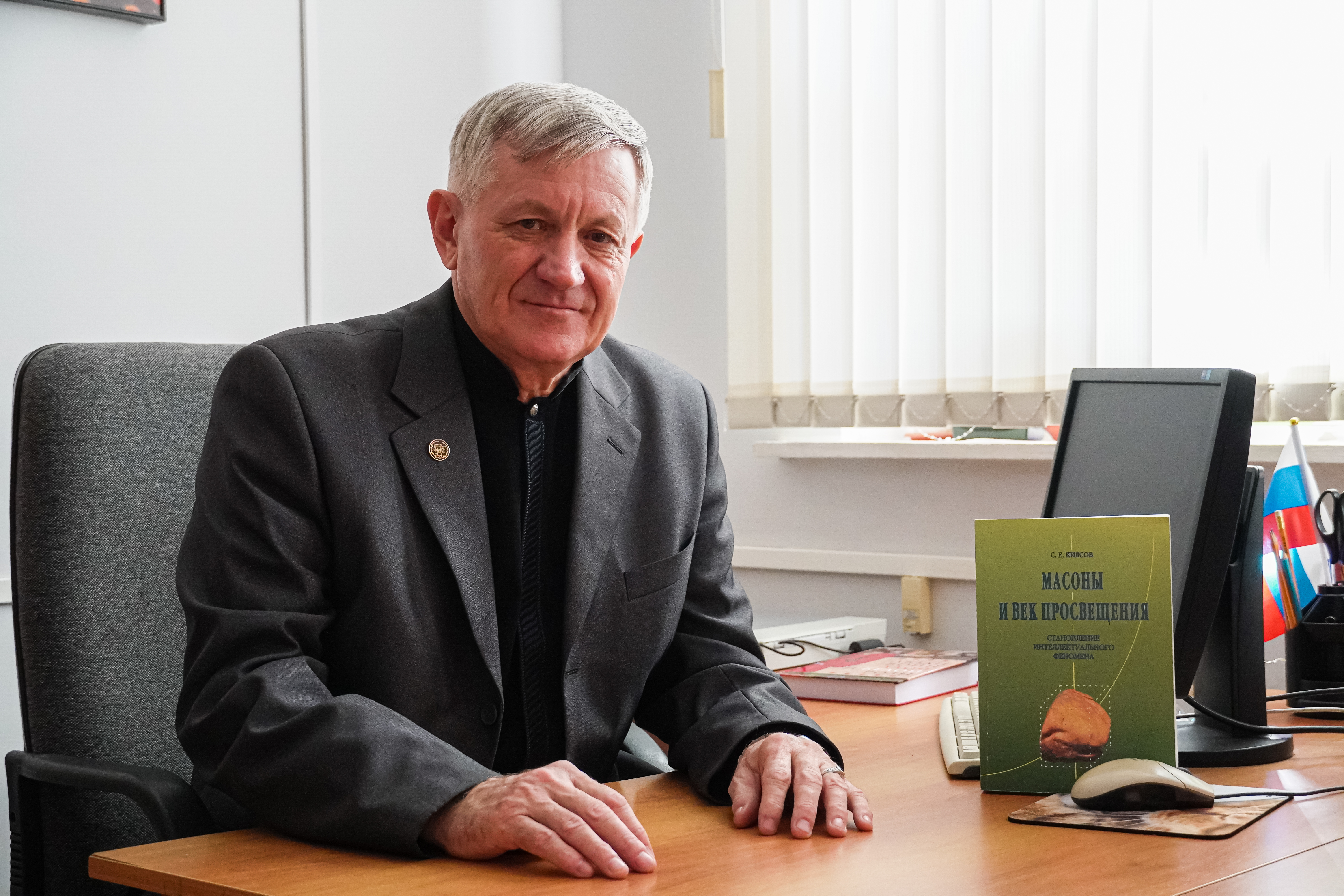

On February 12, Sergei Kiyasov, Professor of the Department of World History, celebrates his anniversary.

Sergei Kiyasov has actively been developing a scientific direction related to the study of social and political thought of the West in modern history and successfully attracting young researchers to work. He has published about 100 research papers, including 5 education-to-methodology guidebooks, 4 author's, and 5 collective monographs.

Prof. Kiyasov is a member of the Russian Society of Intellectual History and the Association of Historians of the 18th century and a member of the SSU Academic Council on National and World History.

Sergei Kiyasov is a representative of a small group of Russian scholars studying the origin, development, and affairs of the Western European Freemasonry. This movement has been shrouded in mystery for a long time, and an atmosphere of a worldwide conspiracy has been formed around its private meetings. The reason for his choice was obvious – to make the history of the freemasons more understandable and present to the interested public a scientific interpretation of their affairs in different eras.

Sergei Kiyasov shared his memories of his professional career as a historian and teaching staff member lasting more than 40 years. As it turned out, in addition to studying the Masonic movement, he is interested to the broadest historical issues – from the birth of the Russian state to the geopolitical doctrines of the twentieth century. He also spoke about the current directions of the development of Russian historical science.

Studentship and beginning of the researcher’s career

– Have you known since you were a teenager that you would connect your life with history?

– I can confirm that I have been interested in history since childhood, I especially liked military history. I even had my own plasticine army. I also read books about Napoleon, about the wars and conquests of Ancient Rome. Before entering the university, I had read many books about important historical events. My hobby was not accidental – I was born after the end of the Great Patriotic War, our family had its own tragic losses – maybe this contributed to my interest in history.

– How did you get into the Faculty of History?

– My family lived in Cheboksary, but there was no university suitable for me with a faculty of history. I took a reference book for applicants, and I liked Saratov State University. In 1971, I came to this city, but I failed to enroll in the full-time course. I scored 18 points in the exams, and I had a pass mark of 19. I chose the correspondence course, was drafted into the army, and served in Transcaucasia, in a climbing company.

– Already in your first year, did you decide on research interests related to world history?

– After the army, I studied in the evenings of the Factory of History, SSU. When I was a third-year student, I enrolled in a special seminar with a young, talented supervisor, Dzhuchi Tugan-Baranovskii. We studied the social and political thought of revolutionary France. Then I chose the main character for my future PhD thesis, the educator Sylvain Marechal. In 1980, I received a diploma with honours, and I was invited to the Department of Modern and Contemporary History. This is a rare case, because it was very difficult to get to the department, even from the full-time courses. But I have showed myself well – I worked actively, wrote articles, and reported at conferences. In Leningrad, I met a leading historian, Professor Vladimir Revunenkov, and in Moscow I met an equally famous scholar, Professor Victor Dalin.

– Did you understand in advance that you would connect your life with science?

– I had no such plans, because, as I have already noted, it was difficult to get to the department. This was a matter of chance. But the then Chair of the Department of Modern and Contemporary History, Professor Igor Parfyonov, offered me the position of an assistant, and my scientific and teaching career began. After successfully presenting my PhD in 1984, I began to do administrative work – I was appointed the deputy dean for correspondence courses at the Faculty of Economics. I took this difficult, time-consuming post for 10 years. After that, I “stepped up” and started writing my doctoral thesis. However, I had to perform administrative again – from 1998 to 2002, I worked in the Central Admissions Committee of SSU as Deputy Executive Secretary of the CAC and Executive Secretary.

– And yet you started doing research and teaching. Were you interested in world history when you were a student?

– Yes, I was interested in the French Revolution, in particular the “conspiracy” of G. Babeuf. In the 1990s, I began studying the history of the Masonic movement. Later, after publishing a series of studies, I became the author of articles about Freemasonry in all the latest Russian encyclopaedias.

Freemasonry studies

– You successfully presented your doctoral PhD in 2008, entitled Freemasonry in the Age of Enlightenment (genesis, ideology, evolution, status). What do Masons do and have their traditions changed over the years?

– Many customs have been preserved. When I was on a business trip to France, I was invited to a (non-working) lodge to get acquainted with the situation, with its design. It became obvious that the initiation system works the same way as before. The most important thing in the affairs of Masonic structures is not esotericism or ancient rituals, but the opportunity for communication and exchange of opinions for representatives of the elite. Technically, anyone can become a Freemason, even the simplest, uneducated person. However, initially, the lodge became a platform for discussing important topics and making coordinated decisions. In the UK, many representatives of the ruling elite joined such a dialogue.

– What tasks did the members of the Order set for themselves?

– The Freemasons anticipated the modern policy of “soft power”, they spread their worldview everywhere, which initially corresponded to the ideals of the Enlightenment. French enlighteners (S. Montesquieu) communicated with English Freemasons, and then opened similar lodges in their homeland. This practice contributed not only to the spread of Masonic structures, but also to the establishment of a new ideology, which undermined the feudal-absolutist foundations of the “old order” in France, and brought the revolution closer.

– Is it true that it was the Masons who prepared the French Revolution?

– The Masons were the bearers of an advanced, enlightening ideology, but there is no need to talk about their conspiracy, which prepared the revolution – there were many opponents among the freemasons. Masons did not participate in the French Revolution as an organised unit, since many Masonic structures (for example, the Great East of France) were under the control of the ruling dynasty. But, of course, their beliefs shaped democratic public opinion.

– How did this movement develop in Russia?

– Just like in Europe, but mostly under external control. One of the first Freemasons in Russia was Peter I. By the way, he met in London with the architect Christopher Wren, a supporter of the creation of the renovated Grand Lodge of London. After Peter's death, English court lodges appeared in the Russian capital, and later, during the reign of Catherine the Great, and Prussian ones. But in Russia there were no causes for the development of their own Masonic structures – it was a tribute to European fashion.

– What is the current state of the Masonic movement?

– In 2017, the 300th anniversary of the Grand Lodge of London was celebrated - the world's first “mother”, system–forming structure – approximately 5,000 delegates from many countries gathered there. Today, the Masonic Brotherhood unites 5 million people around the world, the largest number of them in the United States. The newest Freemasonry is no longer a secret organization, but a social and political movement with long-standing esoteric traditions, which sets itself primarily charitable goals. In modern Russia, this movement is not developed, and the number of domestic freemasons is small. Their affairs, as in the imperial period, are criticised by the Russian Orthodox Church.

– As a scholar, you study the phenomenon of Freemasonry in a different way. Would not you like to become a part of this society?

– I have never had the desire to join the ranks of the freemasons. I have a pragmatic interest – it seems to me that it is very important for historical science to make this “European project” more understandable, so that society does not have a desire to mythologise this movement, to talk about a conspiracy. My priorities are exclusively scientific. History must be understandable and honest.

Teaching and researching principles

– What do you see as promising directions for the development of Russian historical science?

– Of course, it is necessary to determine the true place of Russia in the historical process. I am convinced that we have inherited a history that was written in the 19th century according to the rules of the West. It seems strange, for example, that our state history lacks its own “ancient” period, and its starting point is the history of Kievan Rus. The tough pro-European choice made under Peter the Great also raises many questions. By the way, one should not idealise the history of the West and imitate it – Russia has its own way. All these issues need to be discussed, of course, without trying to destroy the already accepted system of scientific and historical coordinates.

– The range of your scientific interests is extensive. You are teaching courses on modern history, geopolitics, and the history of the southern and Western Slavs. Your main research interest is not only in history, but also in philosophy and anthropology. How do you manage to carry out such multidisciplinary work?

– So far, it is working, although it is quite difficult. I have to work a lot. I am trying to gather students with a variety of interests around me. I have supervised more than 100 graduates. Also, here have successfully been presented PhD theses. However, there is no interest in Freemasonry among modern students – the topic is very difficult to understand and analyse.

– The history of the West is your major. What are the features of your indulging into this field of knowledge from the perspective of a person who grew up in the USSR and was brought up in the appropriate traditions? Have you encountered a barrier when studying European civilization?

– In the 1990s, it was necessary to abandon some well-established stereotypes of thinking. The fact is that the USSR established a unipolar system of interpretation of the historical process, which we had to follow. Nowadays, a universal view of history is a priority against the background of the escalated confrontation between Russia and the collective West. But all this does not prevent the knowledge of history, on the contrary, you understand that we do not need alien, imposed ideals.

Interview by Daniil Pronin

Photos by Dmitrii Kovshov

Translated by Lyudmila Yefremova